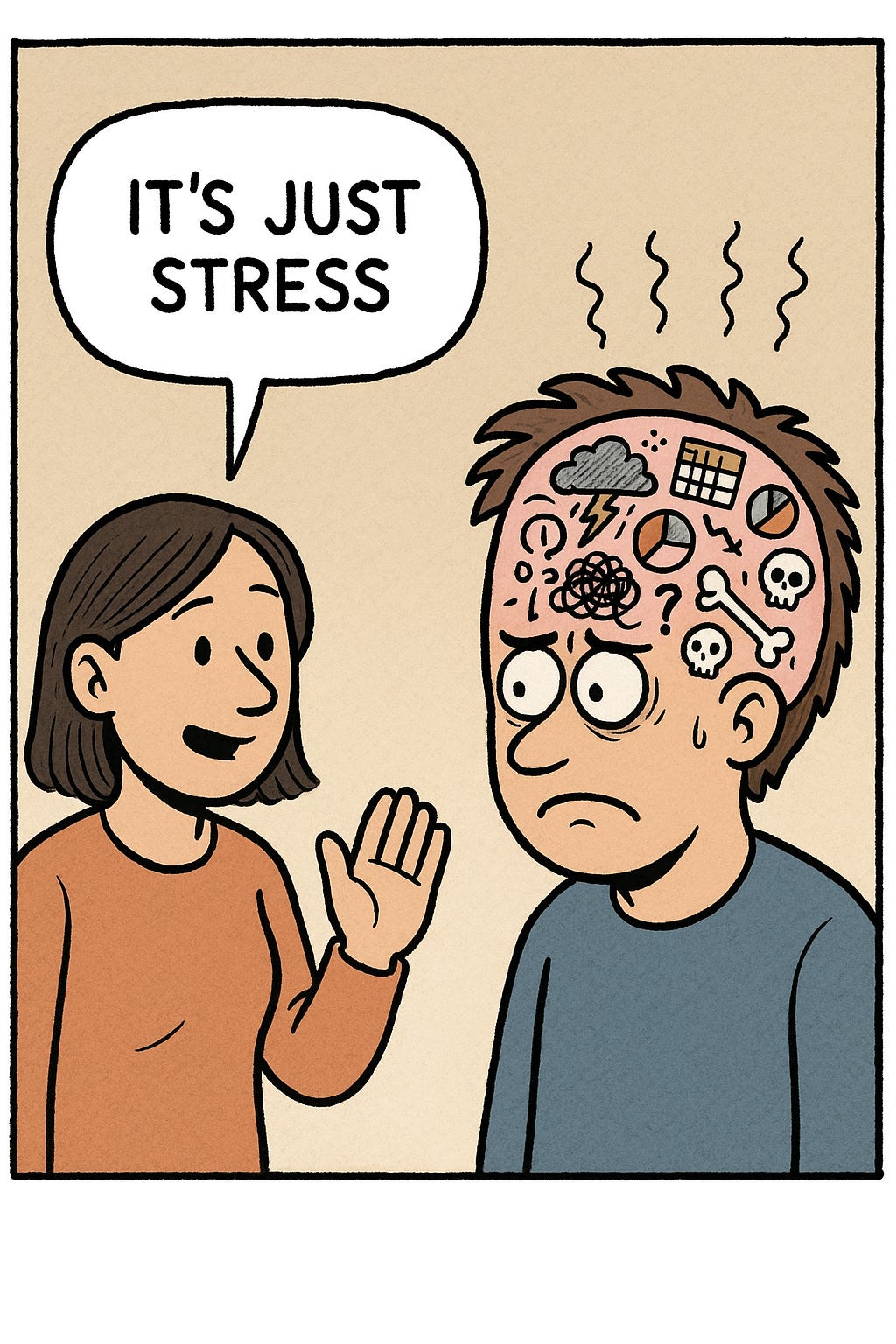

What if the thing killing you or your team's performance isn't stress - but the way you've been taught to dismiss it?

A world-class athlete sits in my office eight weeks before the Olympics, hands shaking, unable to sleep for weeks. Their coach says it's "normal Games year stress."

But this isn't just stress, it's a full-blown anxiety disorder that she has had for years but nobody bothered to ask about. Not treating it effectively will prevent her from succeeding at the Games. But everyone on her team (including herself) dismissed as something "to be expected."

A senior partner at a law firm hasn't slept properly in three months. Everyone keeps saying insomnia "comes with the territory" of leadership.

But the sleeplessness isn't about work pressure, it's a trauma response triggered by an event that he doesn't want to acknowledge had an effect on him.

A 45-year-old female executive experiences chest tightness and rapid heartbeat during board meetings. Her doctor dismisses it as "midlife anxiety" or "just hormones."

Six months later, she has a heart attack. The physical symptoms were real—and treatable—but got lost in assumptions about stressed (aka "histrionic") women.

Normalizing didn't help these people. In fact, it made things worse.

We need to stop pretending that "normal to feel under stress" means "nothing can be done."

And start investing in people who actually know how to look for more.

Doing this will save time, money, and lives.

Think about how we tend to treat physical injuries and illnesses. When a tennis player's shoulder hurts, we assess and treat it. We get MRIs or see specialists to help us assess physical pain from all angles. When an executive's blood pressure creeps up, we monitor and adjust before it becomes a problem. When someone shows early signs of diabetes, we intervene with diet and lifestyle changes.

We treat these physical signs as valuable data to optimize health and performance. We assess properly to prevent bigger issues down the road. We are proactive.

I'm on a mission to help people see psychological signs and symptoms exactly the same way. But somehow we've decided psychological symptoms need to reach crisis level before they deserve attention. That's like waiting for your engine to blow before checking that weird noise.

Meanwhile, these symptoms undermine performance in all contexts just as much, if not more than physical ones. And if we don't be on the lookout for, and treat, mental "injuries" in just the same way we do physical ailments, we lose good talent and good people.

Look, I'm not anti-stress or anti-intensity. High performers sign up for stress and most often thrive on it. Going "all-in" on something you're passionate about isn't the problem. It can be part of greatness. Most high performers live in the "red zone" on the stress scale for periods of time every year and with proper support, they succeed despite it.

But there's a massive difference between the productive stress of pursuing something you love and the destructiveness of untreated mental health conditions.

One fuels performance; the other hijacks it. But we've gotten so used to lumping them together that most people in the high-performance world can't tell which one we're dealing with.

The "Post Game Blues" is a classic example of normalizing before we know what's really going on. It's helpful for describing the emotional let-down after major events, but it can also lead us to miss when something deeper is happening. These reactions aren't unique to sport—executives crash after big deals, students withdraw after exams, and some of it is normal nervous system recovery. But for those with underlying trauma or mental health risks, this experience can go well beyond "natural let down." You can ignore it for a while but for most high performers, the next big event is just around the corner. Why wait to check it out and get the proper help?

When we are so quick to normalize an emotion, we are making assumptions about each individual’s thoughts and feelings. And we miss things.

Remember: High performers are, in fact, "performers." They are masters at hiding emotions. They don't exactly advertise their vulnerabilities and fears. So people think that high performers are okay because they are telling you they are. But some can't just 'push through' the feelings. Or just 'get busy.' Or even just 'ride it out.'

So normalizing and accepting the feelings is not enough. Only a properly trained professional can figure out what will help.

In the case of Michael Phelps, for example, he was silently considering suicide despite just becoming the most decorated Olympian in history.

I know so many high performers who felt like they couldn't ask for help at moments like this. They feel shame about what they're feeling. About saying they can't move on or persevere. Especially if they have all the "accolades" of success and can't explain why they feel so bad. They feel like they "should be happy."

And here's where leaders, coaches, managers, partners, and support teams have a crucial role to play.

Instead of reassuring someone that their symptoms are "normal," what if we got curious?

What if the coach asked, "That sleep issue might be more complex than game nerves -- why don't we have someone who understands sleep disorders take a look"?

What if partners or managers said, "Those panic-like symptoms during presentations could have several causes -- it's important to get someone who can properly assess what's going on."

It begs the question what people are afraid of by asking and suggesting they get a more thorough assessment. There are assumptions about what mental health specialists do (as if we will make it worse by naming what’s going on).

But here's the key: you wouldn't trust your heart surgery to someone who only knows band-aids. So when it comes to psychological symptoms, I highly recommend you find a trained clinical psychologist who understands the full spectrum of mental health concerns - not an executive coach who knows motivation or a consultant who's trained in stress-management techniques. You need someone who can actually look under the hood and spot what others miss. Once you've got a proper assessment, you'll have a better sense of how your coach or consultant can (or can't) help you - and taken together, your team of professional supports will have all the info to help you thrive.

The goal isn't to pathologize normal stress. It's to stay curious about whether someone could feel better and perform better with the right support.

We can still normalize stress in high performance contexts. That's fine. But there is a fine line between stress and distress for most people. Between injury and illness.

So normalizing stress in a world where we still can't talk about it could unknowingly be limiting people's ability to execute to their potential. It's making people doubt their instincts and hide their feelings more. It's making people wait too long to get the help they really need.

Too much normalizing is making people sicker.

And the costs are real. Replacing a burned-out executive costs more than most people's annual salaries. Stress leave, lost momentum, recruitment fees, training replacement talent. Often not finding as good a "fit" for the organization. The tab adds up faster than a lawyer's billable hours and the cost extends well beyond money.

In sport, I've seen athletes wait until 6-8 weeks before the Olympics to finally seek help, only to discover that underneath their 'performance anxiety' is unprocessed trauma from an incident they never told anyone about. But this is not the ideal time to be treating that issue.

Had she been referred to me even 4 to 6 months earlier, we could have relieved the stress and reset the nervous system in time for her to perform to her top potential.

It makes me sad to know that in some cases, “normalizing” an issue for too long has cost talented athletes an Olympic medal and their entire career.

Early intervention can prevent this. It can cost less than a decent laptop and takes weeks, not months.

I've watched athletes run personal best times after we addressed underlying anxiety disorders. I've seen executives make breakthrough decisions once we treated their depression. I've helped performing artists rediscover their creativity when we stopped dismissing their perfectionism as "just being thorough."

Excellence doesn't require suffering from conditions that have solutions.

The interventions exist. They work. Sometimes in just weeks.

We need to be more proactive. We need to look beyond “stress” to ensure we’re doing everything we can to help our high performers thrive.

Because peak performance shouldn’t demand psychological damage as payment.

Something can be "normal" for the context AND improvable.

Part of the territory AND worthy of a specialist's attention.

Let’s make sure normalizing doesn’t mean dismissing and ignoring.

Written by

Heather Wheeler, Ph.D.

...and the Dimmer Switch mentality that helped him excel AND feel whole again

Heather Wheeler, Ph.D.

Seeing the hidden trauma beneath compulsive exercise and disordered eating